A New Headless Site with Gridsome

This post is a bit outdated; this website still looks and works mostly the same, but it’s no longer headless WordPress or Gridsome; it’s SvelteKit. So a few of the smaller features described here, like the search bar, aren’t in place anymore.

There’s a joke (the kind that’s made less because it’s funny and more because it’s true) about developers and designers spending more time redesigning their website than actually doing something with it. Right off the bat, I’ll go ahead and admit I fit that cliché; I’ve had some version of this blog live since 2014, and the number of redesigns I’ve done is uncomfortably close to the number of actual blog posts I’ve written in that same time.

In fact, at the time of this writing, the post I wrote about the last redesign—in early 2018—is still in the top 5 most recent posts on the site. (Yikes.)

This one, though, is at least more than a fresh layer of CSS or a new WordPress theme. This one is taking an entirely new approach: going headless with the Jamstack.

This is going to be a long post, since I’ll go into depth on what headless means, its advantages and disadvantages, some of the techniques involved, and, finally, the design of this site specifically.

What do “headless” and “Jamstack” mean?

Let’s take a moment to break down those terms.

“Headless” WordPress is a bit of a tricky concept to understand—I think in part because “headless” isn’t a particularly good metaphor. But to better understand what I mean, let’s talk about what headless WordPress isn’t.

Ordinarily, WordPress is responsible for both the admin side of the site—where you log in and make changes—as well as displaying the public front-end of the site, i.e., the part that visitors actually see and interact with. It’s a full package; WordPress handles both the creation of your content, and how that content is displayed to users, via the theme generally, and its PHP template files interacting with the MySQL database specifically.

In other words: by default, WordPress just takes care of everything.

If that’s, uh, headful WordPress (see what I mean? It’s a bad term), then headless separates the admin and the front-end, leaving WordPress to handle the back-end content creation and site administration, while freeing the front-end presentation to be handled elsewhere, independently.

So a headless WordPress site will still use the WP backend as usual for all the content management, post creation, data storage, etc. From the admin side of the site, nothing changes, which is probably good news for your clients, as well as anyone who just wants to be able to keep using the admin interface they’re already accustomed to.

But instead of having the site’s theme display your pages, posts, etc., a headless site can use virtually anything, thanks to the WordPress REST API.

If you aren’t particularly familiar with the world of modern front-end development outside WordPress, you might not immediately see the advantages, but there are several to be had. Not being locked into PHP as your templating language means you’re instead able to use powerful, modern frameworks like Vue, Svelte, Eleventy, or—in the case of this site—Gridsome, with all the goodies that come along.

This goes hand-in-hand with Jamstack, and is actually a decent example of it. The JAM stands for JavaScript, API and Markup—though it’s more of a loose description of typical features of a site rather than a literal definition or group of technologies, so don’t get too hung up on those three things. Jamstack sites always use JavaScript in some fashion, but they don’t all use APIs, necessarily.

The term “Jamstack” was coined by Netlify (which, by the way, is where the front-end of this site is deployed). When people say they are launching or deploying a site “on the Jamstack,” that usually means they’re using a host like Netlify or Vercel to compile or “build” their site directly from a git repo, and then host it on a global CDN.

The advantages provided by a headless approach generally boil down to: speed; security; and developer experience.

Speed

As you may know if you’ve ever worked with a very old and/or large WordPress site, waiting for a large page or list of content to load can be very slow, because you’re relying on PHP to both query the MySQL database for the content, and then run the (in)famous WordPress loop to render it.

Using the WP API is typically faster, because PHP isn’t really rendering anything; the site is just sending text data in the form of JSON. And if you use a JavaScript-powered static site generator like Gridsome or Eleventy or Gatsby, that content can even be pre-rendered—building out a full static HTML site from the result of querying the WordPress database, reducing visitors’ wait time to practically nothing.

Using a static site generator (SSG) also means you can deploy all of your site’s content on a global CDN, so it’s immediately available and speedy anywhere around the globe.

Security

The security of adding a layer between your front-end and your database (while, in my opinion, not one of the bigger selling points of the Jamstack) is not to be overlooked. When your front-end doesn’t offer any direct access to the database—and instead, is just a collection of immutable files on a CDN server—that means the methods of attacking your site are minimized. No SQL injections, and you offer no immediate benefit if somebody does manage to hack the DB.

With a headless approach, you also have the option of locking down your original WordPress install in ways you might not have been able to when you relied on WP to serve the front-end of your site.

That said, security probably shouldn’t be your biggest reason to move to the Jamstack, since it’s a tangential benefit, and since it won’t solve bad WordPress security to begin with.

Developer Experience

Finally, working with modern frameworks like those mentioned above (though there are many others) is often more enjoyable for developers, as it allows you to introduce more modern tooling into your workflow, both in how the code is built and how it’s deployed. (Typically, Jamstack sites are set up to deploy directly from a git repo, so that every time you push to the repo, the site deploys the code automatically, saving you from ever touching something like FTP.)

Naturally, developer experience should be the least of our concerns; our users’ experience with the site is more important than ours. But if we’re being responsible with our choices, developer experience should ideally help translate into better user experience, too.

Headless WordPress drawbacks

You might be wondering at this point if there are disadvantages to going headless. And the answer, in a word, is: yes. There are distinct and often significant tradeoffs for the speed, security and dev ergonomics that come with headless architecture.

Less control over appearance from WordPress

By far the biggest drawback, in the case of WordPress, is that your site’s theme—as well as pretty much any plugin that does anything on the front-end of the site—will be rendered effectively useless, at least as far as its user-facing functionality. With headless, since your front-end isn’t rendered by your theme’s PHP template files anymore, plugins that change the appearance or layout of the site will lose their effect.

Actually, the drawback isn’t limited to plugins and themes; core WordPress features, like the customizer, widgets, and nav menus (basically, the whole Appearance tab in admin) will be rendered powerless by a headless setup.

Greater hosting needs

Another drawback is that you’re essentially hosting the site twice. Like I mentioned, I have the front-end of this site on Netlify, which has a free tier, so I’m at liberty to continue using whatever WordPress hosting I want without it costing me any more. (At least, not unless this blog really blows up for some reason, which seems very unlikely.) But that might not be the case for you, depending on your site’s traffic and needs. And then again, hosting isn’t costing me any less, either.

And if you are pre-rendering content with an SSG (as opposed to querying data from your WP site’s API on the fly), you’ll need to redeploy the site each time content changes. (There are plugins to solve that particular pain point, though.)

Tricky DNS setup

Something else to keep in mind: DNS is going to require some careful, likely much more complex setup with headless (more on that later), and unless you do some fancy stuff with your theme and DNS, post previews won’t really work anymore.

Fewer hosting features are relevant

You might also be giving up some luxuries provided by your host, such as staging sites, for example. (You can still use staging, of course, but what you see there won’t match what you’ll see on the live headless site unless you do a lot of extra config.)

Those tradeoffs probably sound very scary, and for a lot of WordPress users, they make moving to headless a non-starter. That’s ok. Every site has different needs, and if sticking with the WordPress you’ve come to know and love sounds like your best path forward, rest assured you’re not alone and you will not be unsupported in that choice.

Why I chose headless

I’ll be honest: this is my personal site, and as such, I treat it a bit like a playground to try new things and generally do whatever I feel like, development-wise.

I really enjoyed this post from Ethan Marcotte, ”Let a website be a worry stone,” which (to crudely summarize) advocates for developers to spend less time chasing perfection in their sites, and instead, treat them like a “worry stone,” i.e., as something to rub the rough edges off of bit by bit over time (and as a necessary and healthy distraction when one is needed).

That’s part of what made me go all-in on Gridsome. I’d been messing around with it (and its WordPress starter) for close to a year when I read that post and made the decision to dive in.

I’m a huge fan of Vue, so Gridsome being a Vue-based framework was a big selling point for me, even though Gridsome itself is relatively immature, at only version 0.7 at the time of writing (which I’ll admit led to some frustrations in the development process). I’ve seen enough sites powered by Gridsome, and enough interest in the community, to abandon worry, however, and jump in anyway. But originally, Gridsome’s blazing speed and powerful, straightforward features sold me. It makes building fast sites both easy and enjoyable.

Gridsome doesn’t need a back-end like WordPress, though, and I toyed with the idea of moving away from WP altogether and making my site fully static, writing new posts in Markdown rather than in the WordPress editor (particularly given my recent frustrations with WordPress’s Gutenberg editor). There’s a strong appeal to just having everything live together in the same repo, and giving up on a database altogether. (Wes Bos and Scott Tolinski have some good podcast content on this in the episodes of Syntax FM covering their personal blogs.)

Eventually, however, I decided it was worth keeping WordPress around for a while, for a few reasons.

One is: I still want to see where Gutenberg goes. The block editor is still a long way from where it needs to be (and I still tweet out my frustrations with it from time to time), but it’s also very exciting.

The block editor, it turns out, is also the best link between a headless back-end and its decoupled front-end.

I came across a plugin called Block Lab, which I highly recommend whether you’re using headless or not. Block Lab beautifully simplifies the process of creating basic custom blocks for use in the Gutenberg editor, and the accompanying PHP mini-template files (component files, I suppose you might call them) which render the content of those custom blocks.

I thought this was amazingly handy given the editor’s lack of some types of blocks that I wanted to create, and it was when I began putting this plugin to use I realized that custom blocks will be custom on the headless front-end, too.

That is: when custom Block Lab blocks are used in page or post content, all of their custom template code comes with them, even through the WordPress API.

That’s very cool, because it means I can still create custom blocks without really needing to build them twice; all I do is put a class in the PHP template file for the block, and target that class with CSS on my headless front-end.

And as a really cool feature: Block Lab checks your theme for a blocks.css file which, if present, loads in the editor, too! So you can style your editing experience as easily as the front-end experience, if you so choose. Realizing that going headless didn’t mean giving up the power of a fully customizable block editor was a big persuasion in sticking with WordPress.

I also mentioned earlier that there are plugins available to rebuild your site on Netlify every time your WordPress content changes (I’m personally using NetlifyPress at the moment), which makes the transition easier, too. Knowing that I can keep my editing process fully in WordPress, without the need to open a completely separate dashboard any time I want to publish or update content, makes things a lot easier.

Another reason, though, is that even though the site is headless, the WordPress REST API can still be live and fully available.

With a typical Jamstack site, dynamic things such as search forms—any type of form, really—can be problematic, as you don’t typically have a database to query (though you could). Typically, when using a static site generator, the best you could do would be to pre-generate category or tag pages, or try to filter content client-side. But either of those approaches still fall short of a genuine search experience.

Keeping my WordPress site live means that I can have the best of both worlds in this regard; I can pre-generate all my content, and I can also allow custom on-the-fly searches that’ll be backed by the WordPress API.

In addition, I don’t need to worry about porting my WordPress site’s RSS feed; I can just point the /feed URL back to the original WordPress site and keep using the same one I always have.

All of this flexibility is actually what sold me on sticking with a WordPress back-end, rather than going fully static. I knew that if I couldn’t get a good form solution going on the Jamstack, I could always just use DNS to point a page back to WordPress and slap a Ninja Form on it, the user being none the wiser. (As it turns out, Netlify does have a rather nifty forms solution, but I like knowing that I can fall back to WordPress for anything I’m not finding or not comfortable with on the Jamstack.)

The new site

I’ve done so much talking about the tech behind the site I haven’t even mentioned the site itself!

Obviously, I liked my old brand (I designed it, after all), but I felt it was maybe aging a little—not necessarily in appearance (though that, too), but more just in terms of reflecting and expressing who and where I am.

It sounds silly, but in late 2017/early 2018 when I was launching the last site, I was in a very, very different place in my life and in my career. (I was neither a dad nor a full-time developer at the time, as the main examples.) The old look was fine, but it didn’t feel like it represented who I am as well as it could anymore.

Naturally, being a designer and a font hoarder, I spent days scouring my library, comparing typefaces and pairings before eventually settling on Pensum Display Basic and Averta Standard as the new typefaces of choice (along with MonoLisa as the font used for code). You can see them all and try them out on the /uses page.

One of the uses for (at least some of) those fonts: code and preformatted code blocks. I anticipate including blocks of code in more of my blog posts going forward, so I thought I should style those blocks up appropriately. This is done with Prism, a lightweight and customizable JavaScript library for code highlighting. I’ve set it up to mirror my actual VS Code preferences.

Want to get super meta? Here’s what a code block looks like on this new site, along with some of the CSS rendering it:

pre[class*='language-'] {

padding: 4rem 1rem 1.5rem;

margin: var(--halfNote) 0;

overflow: auto;

border-radius: 0.3em;

position: relative;

}

pre.language-css:before {

content: 'CSS:';

}This site may load up to six fonts on a page, which is admittedly quite a few by web standards. I didn’t want to compromise on the design, though, so I used other means to mitigate the performance impact, including subsetting each font, conditional loading, and setting font-display: swap to avoid invisible text.

This change in fonts also necessitated a redesign of my personal logo, since the old one wouldn’t have fit with the new look and feel.

I’ll be honest: every time I create a new version of my logo, I feel less and less pressure to make it “something,” and instead just go with what feels right to me. I suppose you could view this either as atrophy or maturation of my design skills; I’ll let you be the judge of that. But in any case, this logo is a little bit of a remix of the last one, but doesn’t try quite so hard to wink at you (at least, not until you hover on it in the site header).

As a nice side effect, the old favicon uses two pairs of brackets, where the new one uses only one, which makes it easy to distinguish between the secondary back-end (where I didn’t bother updating the favicon) and the primary front-end at a glance in my browser tabs.

For the projects, I actually did decide to use Markdown files. Each project, on the “back end,” is a .md file in my repo, with frontmatter for the title, category, etc., and the content in the form of Markdown. This lets me do some fun things with filtering, sorting, and templates to view the projects, and also allows me to play around with more of Gridsome’s features, dipping my toes in the water of what moving to a fully static site might look like.

Speaking of fun things: I tried to put something interesting (interesting for me to build, at least, if not for visitors to look at) throughout the site. There’s the aforementioned font tester on the /uses page, the search feature on the /blog page, and also, a very pointless and highly subjective chart of my professional skills on the about page. (There’s also a bit of cheekiness to be found in the footer.)

On the topic of visual interest: the new site generates a bit extra using a couple of custom editor blocks; Callouts (which work a lot like pull quotes from a print publication), and Highlights (which serve to enlarge key pieces of text). Both make the posts a bit more skimmable (not a word; I’m ok with it), and help convey its main points at a glance.

You’ve probably seen both of them in this article already, but not if you’re reading this on mobile. Callouts repeat text, which is confusing when you’ve only got a single column on a mobile screen, so I hide those at mobile widths. When you’re on a wide enough screen, the callouts appear with the article text conventionally wrapping around them (and hidden using ARIA to prevent screen readers repeating the text).

Highlight blocks aren’t present on the site any longer (save for this page) since it didn’t seem to make sense to have two different ways to call out text, and the styling conflicted a bit with headings. Instead I settled on a different solution to the “repeat reading” problem described above (I stopped caring), and combined both blocks into one.

Highlights, in either case, only appear as larger text (no different to screen readers, since it didn’t feel like emphasizing entire sentences or paragraphs was probably the right thing to do), though they’re styled a bit differently on mobile, just to fit their surroundings better.

The colorful square grid on the header and footer were really the heart of the visual aspect of the design, and they grew out of a typographic experiment I made on CodePen. I realized early on that the site was pretty stark and needed just a pop of color and interest, so I plagiarized myself and reused that colorful grid, and just for fun, made it re-render itself into a new random shape on every new page load.

Speaking of page loads: I experimented with many, many different animations and transitions on the site before finally settling on the advantages of the current setup. There was a time I had full in and out transitions for the pages, but that required some custom setup that eventually I decided was too much of a burden—especially because the “out” transition effectively slowed down the site.

The old sidebar is gone, but there’s room to bring it back. I liked the offset layout.

Meanwhile, I enjoyed adding some new accessibility features. The “skip to main content” link isn’t new, but it’s something I had to recreate, moving away from WordPress.

The site also features a settings menu (which you’ll notice sticking around, pun intended, in the bottom left of the window). This allows you to toggle dark mode and reduced motion on the site. Both of these options detect and default to your own user preference if set (in the case of dark mode, using a CSS media query to avoid a flash of white), but both will override your OS/browser default if you manually toggle them, and store your preferred value in the browser’s local storage. (Which, incidentally, is the full extent of the data this site collects and special permissions it might need.)

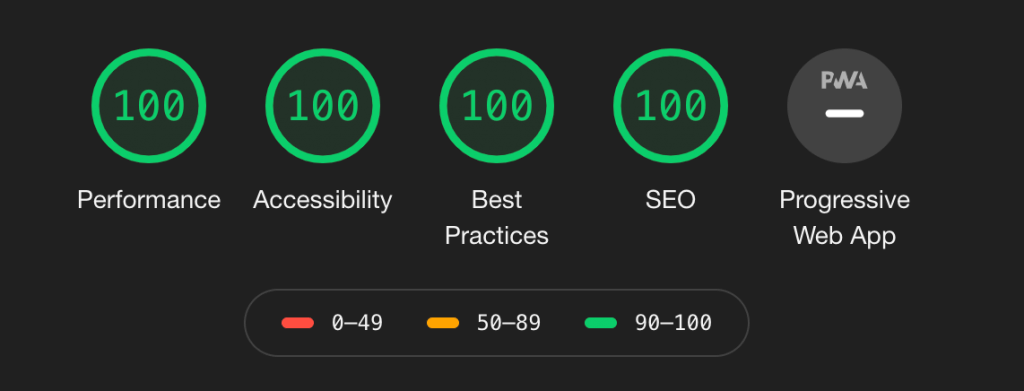

And finally, as far as benefits, I think the results speak for themselves. Here’s the Lighthouse mobile test result:

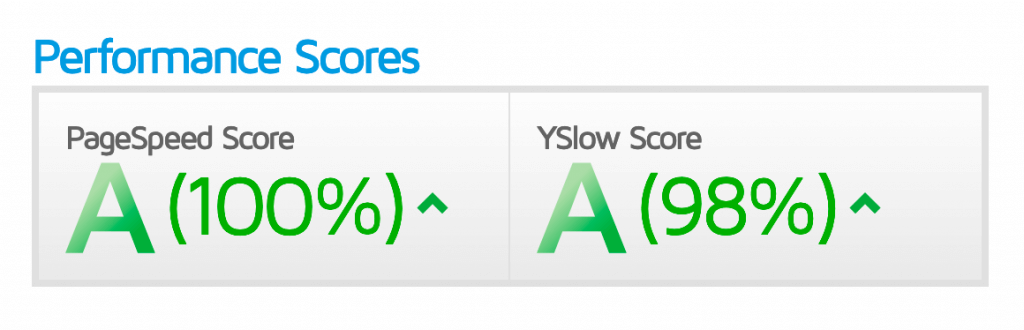

And here’s the GTMetrix score:

Incidentally, the 98% is because YSlow wants me to compress everything, but Netlify doesn’t compress components that are already less than 1kb to begin with. So I’d be trying to bloat a component just to make a speed test happy in order to get that last two percent, ironically.

It may seem like my home page isn’t a good benchmark, since it has virtually no content, and that’s definitely fair. However, note that Gridsome does some front-loading behind the scenes, pre-loading data for all the routes linked on the homepage, so that they can be rendered as quickly as possible once the user clicks one.

What to watch out for when going headless

If you decide to go headless with your own WordPress site, I have a few warnings to consider from my recent experience.

DNS is going to be a complex challenge.

With headless WordPress, you’re effectively coordinating communication between two codependent sites; the WordPress back-end and the decoupled front-end. That requires a cautious and capable understanding of both DNS and WordPress—specifically, the WordPress database.

In my case, there was a pretty considerable slew of DNS changes to be considered, and a search-and-replace of the original site’s database.

Bear in mind also that the original site will need to remain at least partially available (at least, if you plan on deploying more than once), even if you point your main domain to the headless front-end, and crucially, even if you don’t need API access on the original site.

In my case, I pointed joshcollinsworth.com away from the WordPress site and to the headless front-end, but created a separate A record for api.joshcollinsworth.com, and used that subdomain as the access point for the original site.

That gets things working; however, you’ll probably want to make sure WordPress also redirects all traffic that would normally hit the front-end (regardless of domain) back to your live headless front end; otherwise, people will still be able to see the old version of the site and the new one, one on each domain. (This could probably be done with a redirection plugin, but you may want to use your web server’s config directly instead. Either way, it’s going to require a knowledgeable and delicate touch.)

Another DNS warning: you don’t want to redirect any wp-* path. That includes wp-admin and wp-login (so you can still access the original WP site), as well as wp-json for the API, and wp-content to load any images and other assets that may still come from the original site. (At least, not unless you’re planning on downloading all your images and serving them from the same relative path on the headless front end; I decided not to do that in my case, since I already get good image handling from Jetpack.)

Ordinarily, WordPress handles creating responsive images for you with source sets; that’s another thing you’ll lose going headless. Gridsome and other SSGs can help make that up if you serve images from the headless front end, though.

Which reminds me: keep in mind that you’ll be changing things, DNS-wise, to go live with the headless front-end. Odds are, you’ll have at least a few places in your headless site’s configuration that will still be referencing the “live” URL, and you’ll need to deftly handle that during the go-live process.

And it goes without saying, but: if you have email on your domain, make sure you don’t break it with DNS changes. (As long as you don’t change name servers or MX records, you should be safe.)

SEO and redirects

Also: be sure all of your 301 redirects are in place and handled properly, and that you’ve taken care of any other SEO considerations (like adding meta descriptions, for example) before going live with a headless site. WordPress takes care of a lot of things for you in this area (especially if you’re using an SEO plugin), and you’ll need to make sure you’re not shooting yourself in the foot when you go live.

Also, if you have Google Analytics or similar tracking codes or JavaScript loading in the <head> of your site, you’ll need to be sure those get moved over to the new front-end as well.

Deploys are only free to a point

And finally: if you have automatic deploys enabled in WordPress, remember that static hosts tend to charge by the build minute, and that most likely, your whole site will be rebuilt every time you update a post.

Watch those minutes, especially if you (like me) enjoy tweaking posts after they’re published. While some hosts have incremental builds (mostly for Gatsby at this point, as far as I know, since it’s the biggest fish in that particular pond), typically every page and—crucially—each image will be built each time the site is deployed.

The images step is easily the most time-consuming part of this site’s build (Gridsome does some nice things in the build step to minimize image sizes), so keep that all in mind. When your site is static, you need to re-deploy each time you edit content, and there’s a point where that’s going to start costing you.

Thanks for taking the time to read about my headless WordPress site. And by the way, here’s a link to the GitHub repo, if you’re the sort of person who enjoys checking out that sort of thing. (It’s still a little bit of a mess.)

In the end, I had a lot of fun building this site, and I’m excited for it to be live in the world, and to continue smoothing out its rough edges.