I worry our Copilot is leaving some passengers behind

GitHub Copilot was one of the earliest “AI” tools on the market—or at least, one of the first I was aware of. It came along well before ChatGPT exploded, so I and many other developers got the opportunity to try out these large language models (LLMs) before they really broke into the mainstream.

If you’re not familiar: GitHub Copilot “watches” you code, and makes suggestions as you do. It tries to predict what you’ll want to do, and you can either take its suggestions, or reject them and get new ones. (This all happens in your code editor, but you can also interact with it via a chat input.)

I’ve been using Copilot a lot lately, personally and professionally. I’m generally a big fan; it’s hard to imagine going back to not using it.

That’s because sometimes, Copilot can be uncannily helpful. It can, and does, accomplish in mere seconds what might take me several minutes of focused work and/or rote repetition. It’s excellent at math, at boilerplate, and at pattern recognition.

Other times, however, Copilot is clearly just regurgitating irrelevant code samples that aren’t at all useful. Sometimes, it’s so far off base its suggestions are hilarious. (It regularly suggests that I start my components with about 25 nested divs, for example.)

I assume this is because of a flaw in how LLMs work. They’re prediction engines; they’re literally built to guess. They’re not made to give you verifiable facts or to say “I don’t know” (at least, not above a certain threshold of probability).

Copilot gets its name because, well, it’s supposed to be your assistant; somebody you trust to work with, who has your back. But that’s not always accurate, in my experience.

Copilot is often less like a trusted partner, and more like a teammate who’s as likely to put the ball in your own goal as the opponent’s.

Cause for concern

You know from the title of this post that I’m worried.

I’m not worried about that ridiculous div soup, and things like that. Any developer should know better than to take that seriously.

And yes, I’m worried about the quality of our code…but maybe not in the way you might think.

That is: “code quality” isn’t especially meaningful to me, in and of itself.

For one thing, it’s highly subjective; how do you even measure it? And besides, it’s entirely possible the net effect of Copilot is positive (or at least inert), even if it does make some amount of your work worse, in whatever way you might choose to define that.

Plenty of people worry loudly about LLM tools overrunning the internet with crap, and while I guess you could put me in that group, it’s not because I’m a code idealist. Even if half the code in our software is mediocre Copilot suggestions, I don’t really care all that much, as long as it still works.

That’s what I’m worried about.

I’m worried the global, net effect of Copilot might be that it’s making accessibility on the web even worse than it already is.

I’m worried Copilot might be acting, in the silent, covert way systems often do, as a force for discrimination.

There are plenty of other, similar LLM coding tools out there; Copilot is generally just the oldest and most common. While I mostly only refer to Copilot here, I think this entire post applies to all of these tools.

A real-world example: my simple component

Recently, I set out to build a component to help me generate footnotes on this site. You know; the kind that shows up as a tiny link in some text, and that when clicked, jumps you to the bottom of the page for an accompanying annotation. 1

This is a very simple task, as far as web dev goes. In fact, it’s since-the-dawn-of-HTML type of stuff; all you really need is two anchor tags. (You might reasonably wonder why it even needed to be a component in the first place; I was just trying to automate the numbering.)

This blog is in Svelte, and so some of the code samples in this section will be, too. The syntax in these basic examples should hopefully be close enough to something you’re familiar with to parse even if you don’t know it, though.

As soon as I created the file and started typing, Copilot did all the zany things you might expect: it tried to import a library that didn’t actually exist in my codebase, as well as a Svelte export that I didn’t need at all. It also reached for its favorite bit, and slung an ungodly amount of ghost divs into my editor.

Funny, but not concerning. Ultimately, any dev with any experience at all ought to be able to immediately identify that as the hallucination it is.2 The rest, tooling should spot, even if you didn’t.

As for the relevant bits of code, I’d expect most any competent frontend developer should probably know something like this markup (maybe not this exactly, but something in this general shape) is the proper solution:

<a href="#footnote-1" id="link-1">1</a>

<!-- ...Somewhere down the page: -->

<ol>

<li id="footnote-1" tabindex="-1">

My footnote content

<a href="#link-1">Back</a>

</li>

</ol>If you wanted to make this even simpler, you could make links target each other’s IDs. Then you wouldn’t need to add any attributes at all to the list item.

Just links doing link things. Good old-fashioned HTML.

But for this dead-simple task, GitHub Copilot wanted me to add a JavaScript click handler. Something like this, instead:

<script>

const handleClick = (e) => {

e.preventDefault()

const target = document.getElementById('#footnote-1')

target.focus()

}

</script>

<a href="#" on:click={handleClick}>1</a>I hope any good developer would immediately spot this as categorically bad code.

For one thing, there’s no reason to use JavaScript here; the link tag literally exists to do what all this JavaScript is trying to do.

For another, a meaningless href="#" attribute is an accessibility (a11y) mistake all on its own, on top of bad UX. It means users can’t share the link, see where it goes, open it in a new tab, or use it without JavaScript. Assistive technologies probably wouldn’t be as helpful with this as they would be with a real href, either.

Copilot was essentially advising me to make my own, worse anchor tag with JavaScript, instead of just using what the browser already has.

This implementation shouldn’t even warrant consideration, because the path is absolutely fraught with peril, for me and for my users. If I keep going, I’ll be on the hook for all kinds of behaviors and use cases I probably won’t anticipate, and probably won’t handle entirely correctly even if I do.

At absolute best, I’ve done a bunch of extra work just to make my bespoke anchor tag work the same as the one that’s shipped with every browser ever for free.

In short: you shouldn’t reach for JavaScript if you don’t have to, and you shouldn’t override browser default behavior without an extremely good reason.

A second attempt

Ok, so I got a bad suggestion. Maybe Copilot didn’t actually understand what I was trying to do.

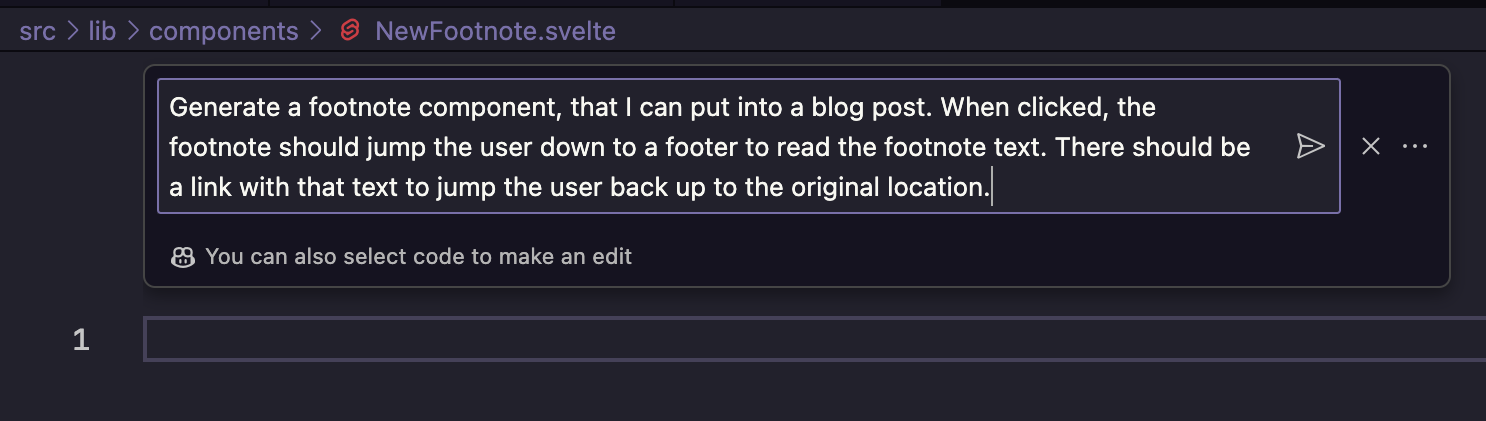

I decided to give it another shot, this time via Copilot’s helpful chat interface. I spelled out my intentions much more clearly this time:

It could probably be a better prompt, but it’s clear enough, I think. Here’s what I got back (I took the time to transcribe it, rather than showing a screenshot, because I think it’s good to see):

<script>

let showFootnote = false

function toggleFootnote() {

showFootnote = !showFootnote

}

</script>

<div>

<p>This is some text with a

<span

class="footnote"

on:click={toggleFootnote}

>

footnote

</span>

</p>

{#if showFootnote}

<div class="footer">

<p>

This is the footnote text.

<a href="#top">Back to top</a>

</p>

</div>

{/if}

</div>You might notice this code doesn’t even do the right thing; I asked it for a footnote, and I got a conditional click handler demo. But egregious though it is, that’s not even the part I’m concerned about.

This is a thoroughly inaccessible solution. It’s a click handler on a non-interactive span element. For one thing, as above, this blocks users who don’t have JavaScript enabled. That might be necessary for some things in web software, but certainly not for this.

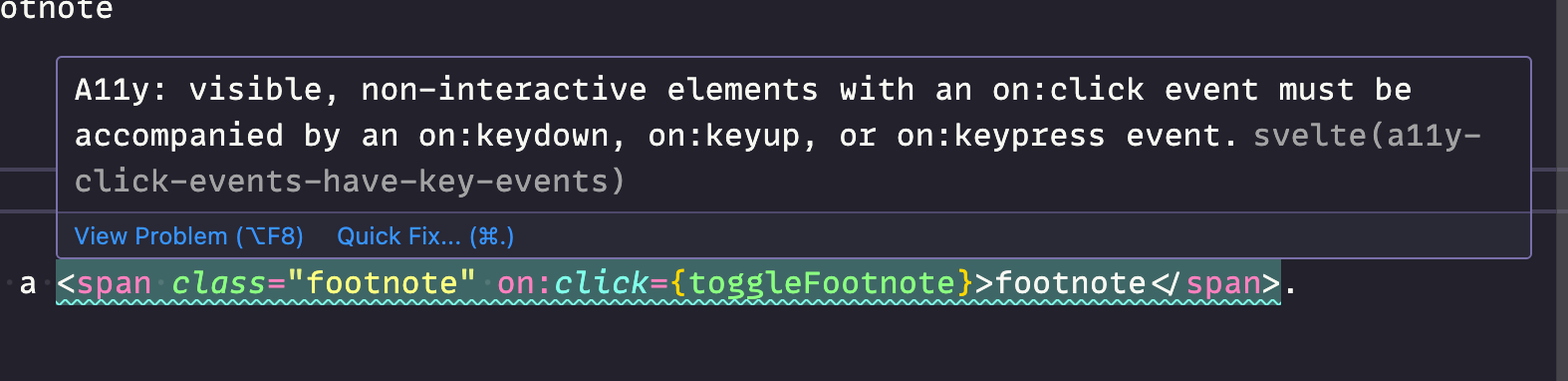

More importantly: this is an extremely basic a11y violation. It’s so simple and so obvious, even the Svelte VS Code plugin warned me about it:

That span isn’t focusable, so keyboard users can’t tab to it or activate it. You need a pointer device, which may or may not include any given assisted technology interface.

Plus, there’s a whole slew of other problems with trying to make a non-interactive element behave as a link or a button. It won’t be as perceivable, or operable, unless you properly consider and handle a whole world of use cases. Like the link above, it’s way harder, and best-case, you just wind up back where you would’ve started if you’d used the proper HTML to begin with.

What does it say about Copilot’s knowledge of accessibility when it will hand us code even basic checking tools would flag?

Copilot is encouraging us to block users unnecessarily, by suggesting obviously flawed code, which is wrong on every level: wrong ethically, wrong legally, and the wrong way to build software.

I know we’re not supposed to hold so-called AI3 tools responsible for their flaws. “They’re not perfect” may as well be the tagline for LLMs.

But if we’re giving one of the world’s major corporations our money, in exchange for this tool that’s supposed to make us better…shouldn’t it be held to some standard of quality? Shouldn’t the results I get from a paid service at least be better than a bad StackOverflow suggestion that got down-voted to the bottom of the page (and which would probably come with additional comments and suggestions letting me know why it was ranked lower)?

Copilot is now responsible for a large and ever-increasing percentage of the code being run on devices all across the planet.

How can we possibly find it acceptable that this tool is unreliable at best, and actively harmful at worst?

Attempt number three

I tried prompting Copilot a third time. This time, I was extremely explicit about what I wanted. I made sure I described very clearly two anchor tags, with href attributes that point to one another’s ids.

I’m not going to bother posting the result I got here, because it was more of the same. <a href="#"> with JavaScript to do all the work. At least all the tags were right this time, even if the implementation was obviously bad.

Another solution with most of the same problems, so clear that my editor already had them underlined.

The burden of responsibility

Some might be inclined to defend Copilot here, and place the responsibility of code quality (in all its forms) on the developer. There’s a certain amount of fairness to that position. After all, I’m the one with the job, not the computer. Shouldn’t I be the gatekeeper? If the code is bad because of a tool I used, isn’t that at least partially down to my wielding of the tool?

Again, this is a fair argument. But not all that is fair is practical or equitable.

It’s pretty obvious things like 25 nested div elements are a wild malfunction (sorry, “hallucination”). I’d expect pretty much anyone to turn a skeptical eye towards that suggestion.

And for any reasonably competent frontend developer, the other cases above should throw up red flags. But there are a lot of issues here.

Let’s start with the historically abysmal track record developers have when it comes to identifying inaccessible code.

It seems like every year, we get a new study showing that somewhere around 99% of the internet has accessibility issues—and that’s just the ones machines can detect. There are way more kinds than that.

Given that current state of affairs, I don’t have a lot of faith in the status quo here.

Besides: there’s a point where a dangerous tool bears some of the responsibility for its own safety.

When the microwave was brand new to the market, and this new space-age technology allowed what used to take 10–20 minutes or more to get done in mere seconds, the manufacturers did’t get to make ovens that stayed on when you opened the door just because the tech was new and revolutionary. They couldn’t claim the user should’ve known better, while allowing their kitchen to fry and their pets to die of internal burns (even though, presumably, most of the people using the new microwaves were previously experienced cooks). They had to build safety features in.4

Products of all kinds are required to ensure misuse is discouraged, at a minimum, if not difficult or impossible. I don’t see why LLMs should be any different.

We wouldn’t even find it acceptable if ChatGPT, or any other LLM, failed to build some basic safety into the product. It shouldn’t fail to give you help if you desperately need it, and it shouldn’t put anyone in harm’s way. (LLMs have done both of those things before, in fact, and faced sharp backlash that led directly to the products being improved. So we know it’s possible.)

Plus, there are far less sophisticated technologies that are fully capable of warning us, or even stopping us, when we’re writing inaccessible or improper code. Why should we just accept that LLM tools not only fail to at least give us the same warnings, but actively push us the wrong way?

Fighting gravity

That constant pressure is my real concern.

Sure, you should know bad code when you see it, and you should not let it past you when you do. But what happens when you’re seeing bad code all day every day?

What happens when you aren’t sure whether it’s good or not?

One benefit of Copilot people commonly tout is how helpful it is when working in a new or unfamiliar language. But if you’re in that situation, how will you know a bad idea when you see it?

Again: I’m not concerned with some platonic ideal of code quality here; I’m concerned with very real impact on user experience and accessibility.

Yes, I would know better than to put a fake button or a link without an href on a page. But what happens when one of my colleagues, who’s not focused on frontend, is using Copilot just to get some stuff out of their way? What happens if that code gets accepted because it’s not their specialty, but it appears to work fine to them?

After all, if I were using Copilot to write, say, Rust or Go, I wouldn’t have any idea whether I was writing good code or not. I’d try it out, and if it seemed to work, I’d move on. I probably wouldn’t even remember what the code looked like five minutes later.

But we know that approach can cause problems on both sides of development. And when it comes to frontend interactivity, the likelihood that blind faith just made your product less accessible is currently quite high.

Here’s another case: what happens if I’m actually a good developer who can spot that violation, but I don’t, because Copilot’s already worn me down like a little kid asking for candy, and my will and focus have been eroded by hundreds of previous nudges?

Any tool that can and will produce inaccessible code is effectively weighting the scales towards that outcome.

If ensuring quality is your responsibility, and the tool you’re using pushes bad quality your way, you are fighting against gravity in that situation. It’s you versus the forces of entropy. And unless you fight perfectly (which you won’t), the end result is, unavoidably, a worse one.

Besides, we probably shouldn’t make assumptions about who can, or will, spot the issues put forth by LLMs in the first place. It’s tempting to dismiss the concern and say “sure, yeah, bad developers will take bad suggestions.”

We’re all bad developers at least some of the time.

None of us is perfect. We have deadlines, and other responsibilities, and bosses who want lots of things that aren’t necessarily directly related to code quality. We’re not all going to spot every piece of bad code that comes across our screen. (Heck, most of us have pushed bad code, that we wrote, on a Friday afternoon.) So when we use a tool that throws bad code our way some percentage of the time, we’re effectively guaranteeing it influences what we make.

The quality delta

Another common argument I see in defense of Copilot is: yes, bad developers will push bad code with it. But they’re bad developers; they would’ve been pushing bad code anyway! And along the way, maybe Copilot actually helps them do something better, too.

Personally, I find that argument unacceptably dismissive. Will some people put bad code out there? Of course. Does that absolve us of giving them a tool to put out even worse code, even faster? I really don’t think it does.

Sure, I gave Mark a beer, but he’s an alcoholic; he probably would’ve been drinking anyway.

Unfair? Maybe. I’m not so sure. I would argue that if you know any number of people will abuse something, you have at least some responsibility to try to prevent it.

In any case, if we know we exist on an uneven playing field (which we do), we shouldn’t see the slant as the baseline. If the status quo is already inequitable (which it is), we shouldn’t see something that’s equally inequitable as just fine, just because that’s the current reality. It’s not fine. It’s just more of the same inequitable slant.

Go back to the section before; if Copilot is enabling bad developers to work even faster, and do more bad things than ever before, on top of actively passing them bad suggestions, I don’t think we can just get away with saying the whole thing is purely the fault of those developers.

A system is what it does. A machine that hands bad code to bad developers is a machine that enables bad developers to stay as bad developers.

The time idealist

Ok, let’s say bad devs gonna bad dev. But some still argue: that’s fine, because now, the good developers are doing much better! And, they’ll have time to make the web a better place, because of all the other helpful things Copilot is doing!

Oh, how I wish the world worked that way, my sweet summer child.

Even if you’re one of the “good devs,” and even if Copilot suddenly makes you twice as productive, as Microsoft (dubiously) claims, your day didn’t just suddenly get half as long. You just suddenly got twice as many responsibilities.

If organizations actually cared about putting resources towards accessibility, they’d already be doing it. They don’t. They care about profit, and the moment you have 40% more time, you’re going to spend 100% of it on something that makes the company money.

But AI will fix what it broke

There’s been a lot of talk about how LLMs will soon be able to fix accessibility issues on the web. And I admit, there is some reason for optimism in this area.

I’ve seen it myself, in fact. I have a common condition known as color vision deficiency; partial colorblindness. Certain parts of the red-green spectrum are invisible to my eye. I can see most reds and greens fine, but certain hues blend together. Light pinks might look white; a lime green might seem yellow; green stoplights just look white; and purple almost always looks blue to me, because I can’t see the red in it. (Actually, I just learned recently the Goombas in Mario games are brown, not red, as I’ve always seen them.)

But I’m a developer and designer, and so working with color is crucial for me. So lately, when I’ve wanted to make sure the color I’m working with is actually the color I think it is, I’ll pop open ChatGPT, paste in the hex code, and ask what color it actually is. “That’s a bright yellow,” it might tell me.

Many think this type of thing will come to browsers, somehow, and will be able to help correct accessibility errors in similar ways. If an image doesn’t have alt text, for example, an LLM tool may be able to describe the image.

Again, I think there’s warranted optimism here. However:

- That’s still a long ways off, if it ever comes;

- There’s no guarantee of how well it will work even when it does arrive (will it describe the image correctly? Will it understand the context, and the vibes of the image? Should it in the first place, if the author left the

altempty on purpose? And by the way, why do we have such faith in an LLM to get this right when we’ve spent this whole time talking about an LLM getting accessibility very wrong? Are we sure we have the cause for optimism we think we do here?); and finally - There’s no credit card for inequity. I don’t think it’s ethically sound to suggest that any present wrongdoing is justified by a future solution that will undo it, especially given points 1 and 2.

What’s the alternative?

The final pro-Copilot argument I’d like to address here is: it’s not any worse than StackOverflow, or Google.

In theory, if you didn’t have Copilot available, you’d go and search Google, most likely ending up on StackOverflow. And there’s no guarantee that what you find in that search will be of good quality, or that it’ll be any more accessible.

That, too, is fair. But I’d point out that by the time you’ve gotten to that answer, you’ve seen at least a half dozen potential solutions (via the search results and the StackOverflow answers). You might come across a “don’t do it this way” headline. You might decide to look at two or three options, just to compare and contrast.

That’s invaluable context. Not only are you now better equipped to understand this solution, you learned more for next time. You’re a better developer than you were.

Not so with Copilot. You gained zero context. You didn’t really learn anything. I certainly wouldn’t be learning Rust, if I were just letting Copilot generate it all for me. I got a workable answer of unknown quality handed to me, and my brain was not challenged or wrinkled in the slightest.

Plus, with StackOverflow, you most likely have plenty of comments and explanations of why one solution might be better than another, or potential pitfalls to avoid. The discussion around the code might well be even more useful than the code itself.

And, of course, it’s all sorted by a voting system that, while certainly not perfect, generally pushes good results to the top, and suppresses bad answers.

You don’t get any of that with Copilot. You get one suggestion: the one the algorithm in the black box decided was the one you most likely want, based on whatever context it was able to glean.

Copilot doesn’t tell you why it picked that suggestion, or how it’s better than the other options.

But even if it did: how could you fully trust it?

Other unavoidable issues with LLMs

There are plenty of other issues with GitHub Copilot, and with other LLM tools, which I haven’t even mentioned yet. They’re essentially plagiarism machines, enabling corporations to profit on unpaid, non-consensual labor. Nobody whose data was used to train these LLMs was, really, allowed any say in the matter. In a lot of ways, in fact, “AI” is just the newest iteration of a very old form of colonial capitalism; build a wall around something you didn’t create, call it yours, and charge for access. (And when the natives complain, call them primitive and argue they’re blocking inevitable progress.)

LLMs have security issues, too. We’ve already seen cases where people’s private keys were leaked publicly, as an example.

Plus, the data they’re trained on—even if it were secure and ethically sourced—is inherently biased, as humans themselves are. LLMs trained on all the open data on the internet pick up all of our worst qualities along with everything else.

That’s deeply problematic on its own, but even more deeply concerning is how these effects might compound over time.

As more and more of the internet is generated by LLMs, more and more of it will reinforce biases. Then more and more LLMs will consume that biased content, use it for their own training, and the cycle will accelerate exponentially.

That’s horrifying for the internet in general, and for accessibility in particular. The more AI-generated garbage is spewed out by marketers trying to game SEO (or trying to churn out content after their teams have been laid off and replaced by AI), the more inaccessible code will proliferate.

On top of all these issues, LLMs are wildly energy intensive. They consume an obscene amount of power and water—and the data centers that house them are often in places in need of more water.

It seems wildly unjust to spend buckets of water on answering our stupid questions, when real humans in the real world would benefit from that water. (Especially when we’ve proven we can find the answers on our own anyway.)

I added this section post-publish because (thanks to some Mastodon comments) I realized I’d completely glossed over these issues, and others.

That’s not on purpose. These issues are every bit as important, if not more so. And if I’m being honest, it sure seems like the world is a more just place without LLMs than with them, for all the reasons above.

The accessibility-in-code angle is one I haven’t seen discussed as much, however, and so I wanted to especially call attention to that in particular.

We deserve better

We’ve casually accepted that LLMs are wrong a lot, mostly without asking why.

Why do we accept a product that not only misfires regularly, but sometimes catastrophically?

Let’s say you went out and bought the new, revolutionary vacuum of the future. It’s so amazing, it lets you clean your whole house in half the time! (Or so the vacuum’s marketing department claims, at least.)

Let’s say you got this vacuum home, and sure enough: it’s amazing. It cleans with speed and smarts you’ve never seen before.

But then, you start to realize: a lot of the time, the vacuum isn’t actually doing a very good job. You realize you spend a lot of time following it around and either redoing what it’s done, or sending it back for another pass.

In fact, sometimes, it even does the exact opposite of what it’s supposed to do, and instead of sucking up dirt and debris, it spews them out across the floor.

You would find that entirely unacceptable. You would take that vacuum back to the store.

And if the salesman who sold you the vacuum laughed in a congenial, but mildly condescending way and assured you that’s how the vacuum was supposed to work, and that’s all totally normal, and that’s just a quirk of these amazing new models; they just “hallucinate” from time to time…

…Well, I don’t think you’d have much faith in that product.

And while I can certainly understand why an LLM trained on all of the internet, with all its notoriously shoddy code, would have some incredibly bad data in its innards, shouldn’t we expect better than this?

The internet is already an overwhelmingly inequitable place.

I don’t think we should accept that what we get in exchange for our money is, inevitably, a force for further inequity, and yes, ultimately, for discrimination.