Classic rock, Mario Kart, and why we can't agree on Tailwind

When my brother and I were younger, our tastes in music were nearly polar opposites. I was a total hipster, and valued what I saw as artistic integrity and creative innovation. I was almost entirely into new and active, of-the-moment artists.

In contrast, my brother made virtually no judgments at all. He was open to anything and everything, but his mainstays centered on classic rock of the ’70s and ’80s. He loved rediscovering decades-old albums by many of the most well-known artists of their time.

Like any good elitist snob, I hated anything popular. So naturally, my brother’s kind of music was anathema to me at the time.

My brother never really understood what it was I seemed to dislike so strongly. So finally, one day, he asked me.

I thought about the question for a minute, and then summarized: “it’s all style and no substance.”

He burst out laughing.

“That’s the best thing about it!” he said with a huge grin. “That’s the whole point!”

I knew we looked at the same things in opposite ways. But I had never realized before then that, wildly enough, we had all the exact same reasons for it.

We don’t disagree where we think we do

Tailwind is nearly as ubiquitous as it is polarizing these days. (I trust if you’ve been interested enough to read this far, I don’t need to cite any sources there.)

Proponents show a near cult-like devotion to Tailwind, some even going so far as to claim it’s “fixed” CSS—or at the very least, made it manageable and predictable in a way it wasn’t for them before. Most frontend frameworks and products feature a first-class Tailwind integration, due to its soaring popularity.

Detractors, on the other hand, claim Tailwind is messy; it gets in the way; it violates core fundamentals of web development; it cuts against the grain; it diminishes the power of CSS; and/or that it does the opposite of what it’s supposed to, adding complexity and making projects even harder to maintain.

Many who use Tailwind never want to go back; many who don’t never want to.

How could we possibly disagree so sharply?

After using Tailwind for a good while now—both professionally and on a few small personal projects—I’ve come to what might just be the most unpopular opinion of all, in regards to that question:

Both sides are right.

…Ok, ok, I can hear the boos. Nobody likes a centrist. But hear me out.

We won’t ever get anywhere debating the merits or flaws of Tailwind, for the same reason my brother and I never persuaded each other on music.

We could’ve dissected Bon Jovi and Sufjan Stevens all we wanted. But it didn’t matter, because our disagreement ultimately started before either one of us ever pressed the play button.

It turns out, he and I actually saw every artist and album in pretty much exactly the same way to begin with.

We just never agreed on what was a feature, and what was a bug.

Likewise, I suspect most people on opposing sides of the Tailwind debate actually completely agree on Tailwind itself. I don’t think our divide centers on atomic CSS, or utility classes; I think the contention comes from valuations we made long before we ever chose our tools. Where one of us sees a selling point, the other sees a flaw.

Tailwind is great.

Tailwind is also a bad idea.

And it is both, at the same time, for exactly the same reasons.

The user defines the tool

If you’ve played Mario Kart 8 Deluxe on Switch, you might know the game offers a feature called Smart Steering.

(Yes, this is still about Tailwind. Bear with me here.)

Smart Steering is essentially an AI copilot. When enabled, you control your racer as normal, except that if you start to go off the road, the game will automatically take the wheel and steer you back on course. No more slogging through the grass, or plummeting off the side of the track.

Smart Steering can help even the playing field among any mixed group (particularly on higher engine classes, where even very good players may find themselves hurling off the track).

But as you get better and better at the game, Smart Steering begins to help less and less…until eventually, it starts getting in the way instead.

Smart Steering will prevent you from taking shortcuts, for one thing; it can’t tell why you’re going off the main road, but it jumps in the way and prevents you from doing so regardless. It may even intervene unexpectedly, pushing you off your intended course at inopportune moments.

You might have a strategic reason in mind for going off the road (maybe you were avoiding a ruinous obstacle, for example), but Smart Steering won’t allow it regardless.

Plus, as a balancing feature, the game’s strongest speed boosts are disabled for players utilizing Smart Steering.

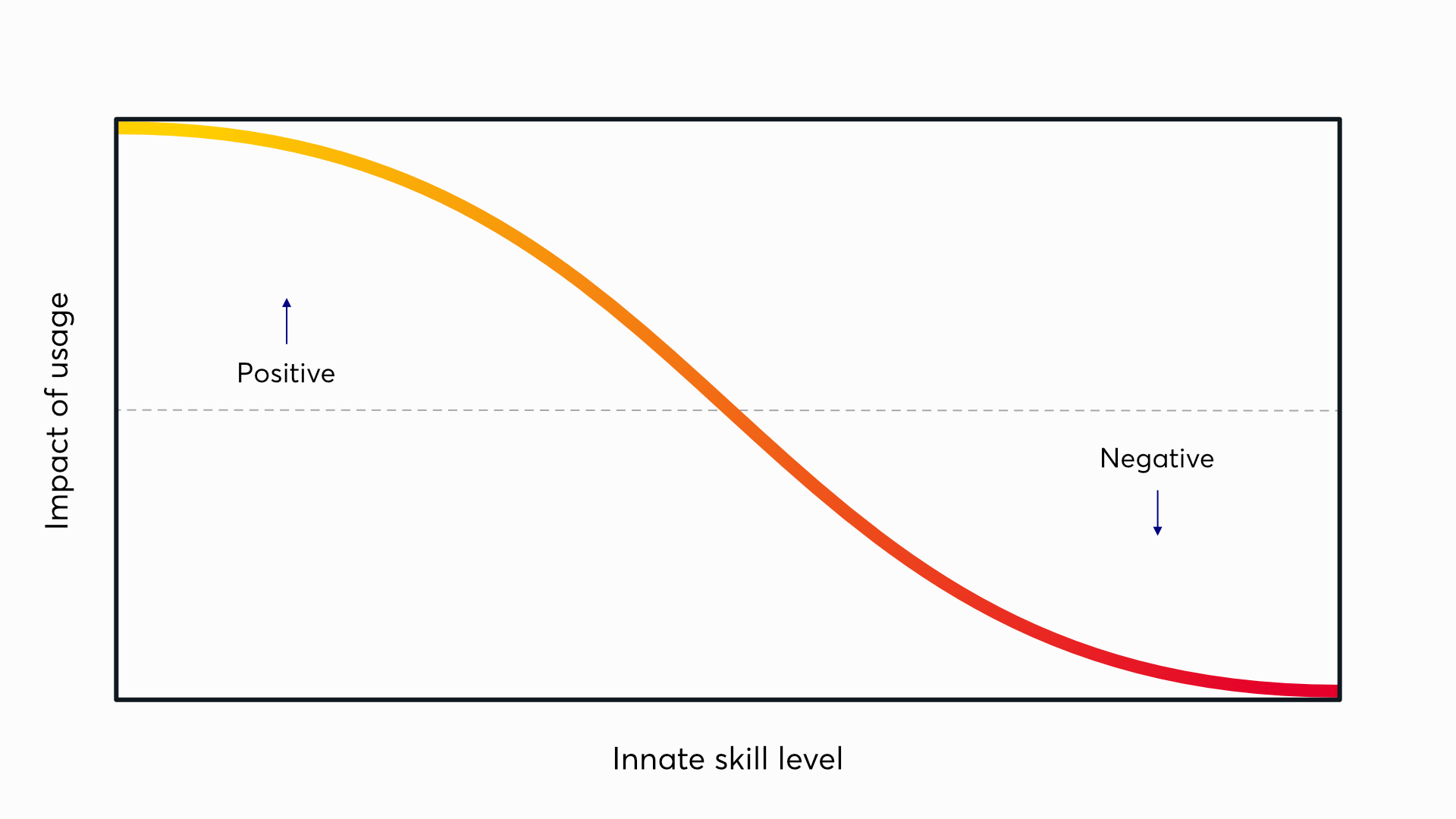

The more skilled you are, the more this feature designed to augment your abilities instead begins to inhibit them. But whether it makes you better or worse—and to what degree—will depend entirely on where you’re coming from.

I’m a very good Mario Kart player (I spent some thirty years of my life playing Mario Kart games before Smart Steering came along, after all), and so I can’t stand Smart Steering. I never use it. I might not notice it a lot of the time—it might even occasionally help me—but what stands out to me are the times it jumps in my way at the worst possible moments.

Smart Steering might keep me on the track, but it also suppresses my fullest abilities. It thwarts the best outcomes just as commonly as it averts the worst disasters.

To those sufficiently skilled with CSS, Tailwind feels like being forced to code with Smart Steering on.

That’s why any conversation I have with somebody who likes Tailwind will probably be like trying to explain why I don’t like Smart Steering to a Mario Kart player who relies on it.

“I don’t like that it keeps me from driving off the track.”

“What!? Why would you ever want to do that!?”

“You can actually skip ahead if you use this trick right here…”

“Ugh, what a hacky workaround. It’s really best practice to stay on the track, you know.”

“Look, I understand why you’re saying that, but I’ve been doing this for a long time, and I know what I’m doing.”

“I just don’t know why you’d make things harder on yourself, only to do something you’re not supposed to do anyway.”

I realize I might sound rather arrogant in choosing this comparison. Mario Kart is a racing game, after all, which might seem to imply that I think of myself as a winner, and people who don’t do things my way as inferior.

That’s not at all my intent; I only mean to point out that if Tailwind is your thing, it’s probably because we’re coming from different places, and like to play the game differently, for our own very valid reasons.

There are no benefits without tradeoffs

For the most part, it’s perfectly fine if we see the same thing in two different, even opposite ways. However, there’s one universal truth I think it’s important we agree on as common ground, namely: benefits always come with tradeoffs (and vice versa).

When it comes to frameworks, at least (CSS or otherwise), any place things seem simpler, we’re actually just experiencing the upside of some architectural decision. That decision, whatever it was, has downsides elsewhere; some other part of the chain, further away from our view, is now also more complex or difficult than it used to be.

Don’t get me wrong; that’s still usually a good thing. The new set of tradeoffs is often preferable to the old set; we wouldn’t use frameworks if that weren’t the case.

But complexity always exists, even if it’s remanded to a place you don’t regularly experience it.

Problems in tech don’t vanish; they simply get reconfigured into new shapes, with new pointy edges in new places.

So we should be incredibly skeptical of any framework (any product, really) that claims to have eliminated complexity—destroyed it, turned it into nothing—without being honest about the byproducts.

Ok, fine. Why is this all important?

Because Tailwind is often marketed (and spoken of by many of its proponents) as a framework that’s achieved this impossible task of obliterating CSS’s complexity from existence.

If you would make this argument, I would firmly dissent. But I would also agree you’re probably right in your case.

You likely don’t work in the areas where the tradeoffs are, so they might seem like they don’t exist to you.

Boring and lazily centrist as it may sound: I think we have to agree that Tailwind and vanilla CSS are both unique sets of tradeoffs. Whether we consider one better than the other will depend very much on where we spend our time, what we value, and what we ultimately consider to be the point of all of this.

Let’s be fair: CSS does have myriad complexities and pitfalls, and Tailwind admittedly smooths out many of those rough edges, in various ways.

But CSS is also an incredibly powerful programming language, which Tailwind diminishes, creating liabilities of its own along the way.

The only invalid point of view is that you can have all benefits and no downsides. It just doesn’t work that way.

It all depends™.

The divide: where do you want to be?

So if what we actually disagree on is what we value, that naturally begs the question: where does this rift come from?

To me, the gap between Tailwind supporters and critics comes down to what part of the job they consider to be the most important—or at least, which part they prefer to focus on.

Because continuing to come up with synonyms for supporters and detractors is tedious, for the sake of this section, I propose we give the opposing groups names. These names will, in themselves, be coarse generalizations, which means they will have obvious outliers and glaring contradictions. But for the sake of a model that is hopefully useful despite its flaws:

Let’s call the generally pro-Tailwind group Builders, and let’s call the generally anti-Tailwind group Crafters.

This isn’t to say that Crafters don’t build things, or that the Builders aren’t skilled craftspeople. But as a quick and messy shorthand, let’s go with it for a moment, because I think it hints at the values of these two groups.

Builders

Builders value getting the work done as quickly and efficiently as possible. They are making something—likely something with parts beyond the frontend—and are often eager to see it through to completion. This means Builders may prize that initial execution over other long-term factors.

Builders tend to tout Tailwind as the saving grace that got rid of the hard parts of CSS. They like that Tailwind makes the work tidy and fast.

That, in turn, strongly implies Builders value getting through this particular part of their work as quickly and easily as possible. (We all value efficiency, of course. But where you value it may implicitly say something about your priorities.)

This also implies one or both of the following: either a) that they found this work overly challenging before; and/or b) that this is not the part of their job they wish to be challenged in. They likely don’t shy away from challenge; they probably just prefer it in a different form.

Again: exceptions and outliers will be plentiful, of course. But: as a group, Builders tend to be people who’ve spent their careers, if not in other parts of the stack, then at least in other areas of frontend. That is: for most Builders (though not all), CSS is not a specialty—or at any rate, not a priority. Many people who like Tailwind are also very good at CSS, but those Builders tend to be bringing a more balanced approach, where they use Tailwind for the broad strokes of utility classes, and heavily customize the config file and/or write their own CSS to fill in the gaps.

Crafters

On the other side, the Crafters tend to be seasoned CSS specialists, and almost always enjoy the part of the work that Tailwind is supposed to make easier. It’s fair to say they’ve overcome the challenge presented by CSS—or, at least, that this is where they like to be challenged.

Crafters may be building holistic products and projects, just like Builders. But Crafters generally are less focused on getting through the frontend as a part of that work, and instead see the frontend as the product itself. They also tend to have views beyond the initial completion of the project.

Because of their skills with (or willingness to be challenged by) CSS, Crafters often see Tailwind as a blunt instrument that dampens their abilities. At worst, Tailwind locks off the best parts of both CSS and of their jobs. (Tailwind can’t keep up with new CSS features, and even where it can, it can’t implement everything or do everything that CSS can.) At best, it represents a hefty learning curve, just to get back to where they already are.

Speed isn’t an issue for Crafters—or at least, not a priority; they are more concerned with the handiwork of their product. Styling is exactly where they want to be, because they value doing the work uniquely well over doing it well enough. Again, they see this work as central and defining to the product, and not just a detail of it.

Crafters are more likely to value long-term factors like ease of maintainability, legibility, and accessibility, and may not consider the project finished until those have also been accounted for.

Builders and Crafters

As Jeremy Keith put it so well: where it comes to styling, Builders want imperative programming; they want to specify what they want, where they want, how they want it. No surprises.

Crafters instead want declarative programming; they understand how to wield the power of creating rules of governance within a complex system, and want to use that power, rather than micromanaging the browser.

Builders value predictability; they will often sacrifice power if it also means eliminating risk and instability.

Crafters value proficiency; they will often accept greater risk and responsibility if it also expands their abilities.

Both Builders and Crafters have fully valid points of view. And in fairness, as I implied earlier, there exists a rich gradient of options between the two. You can balance workmanship and craftsmanship. You can use Tailwind only as much as you choose, and opt to reach for hand-authored CSS the rest of the time.

The question is really just what you value, and where you want to spend your time.

Conclusion: my point of view on Tailwind

To continue using the distinctions above: I consider myself a Crafter. I am, therefore, wary of any tool that nudges me towards building things a certain way—especially when it’s proliferated across my profession, and has become so popular you can tell most websites built with it at a glance.

In my view, the more you optimize for building quickly, the more you optimize for homogeneity.

I acknowledge that Tailwind might be a great solution, if its downsides are not issues for you, or if you have other means of mitigating them.

If it solves your problems, by all means, disregard my qualms as the ramblings of an old man yelling at a Tailwind-shaped cloud. It’s only a tool, after all. It shouldn’t be something we have to agree on if we’re not working together, let alone a pillar of anyone’s identity.

But to me, Tailwind is a problem in and of itself. The tradeoffs may be a net benefit for your use cases, and if so, that’s great. I’ve tested Tailwind pretty thoroughly for a good long while now, however, and I’ve concluded that it is not a net positive in my case.

I don’t mind working with it on a team (it is useful as a unifying system, after all), but at the very least, I request the freedom to break out of it at my discretion as needed and as it’s useful. I feel anyone working with Tailwind should have this autonomy. I’d even go so far as to say you’re suppressing your Crafters if you don’t allow them that freedom.

I do not care how fast I build, or how easily I prototype, so much as I care that I am building something uniquely good, and building it the right way.

Besides: I would argue that the last few years of growth in browser CSS, as well as frontend frameworks, have rendered Tailwind’s benefits largely moot for many use cases. We have @scope in CSS now. We have cascade layers. Even if you don’t want to reach for those from the platform, most frontend frameworks (like SvelteKit, Vue, and Astro) offer scoped styling as an out-of-the-box feature. (Or you can use CSS modules.)

Or, if what you like about Tailwind is the utility classes, there’s the much less intrusive Open Props.

Point is: I think Tailwind served the world of pre-2023 frontend development quite well. I don’t expect fans or organizations to move, but I do think we’re actively outgrowing the need for it right now. Most of the answers Tailwind provided weren’t otherwise readily available at the time, but they’re now becoming more and more just parts of the platform, and of the other tools we’re already using anyway.

Some backstory

There was a time in my career when I, along with the rest of the frontend engineers I worked with, were forced to write absolutely everything in Tailwind. There literally wasn’t a stylesheet to even put CSS into; it was forbidden. We couldn’t even edit the Tailwind config file for most of the time I was there. The powers at that company decided that was the best way to keep us all consistent. If it wasn’t Tailwind, it didn’t ship.

(Everybody I’ve told this to finds it bafflingly ridiculous. Even the most ardent Tailwind fans cite the ability to simply break out of it and write CSS any time as a necessary and beneficial feature. Nonetheless, it was our reality.)

Clearly, there was a sharp lack of representation in the room when that decision was made.

We, the frontend team, tried reasoning with the more senior and more backend-focused developers in charge of this tooling decision; tried to explain why an all-Tailwind, no-CSS approach was not just crippling our ability to execute on our designers’ creations, but forcing us into questionable architecture choices as well. (Custom components proliferated out of control, to the point that it almost didn’t make sense to have components at all. A bustling inline-style-tag-smuggling economy sprung up.)

We also explained how this change was having adverse effects, both on the workers and the work. By putting our best tools just out of reach, we were forced to put more effort into crude workarounds, just to achieve mediocre results.

We weren’t happy, and neither were the designers whose work we were implementing. (Try explaining to a designer that what they want would be not only possible, but relatively trivial, if you weren’t locked into a Tailwind-only world.)

Besides, this just resulted in JIT styles being abused all over the place. The compiled stylesheet on the project had ballooned to unreasonable scale, because every team was just implementing their own one-offs willy-nilly.

Both the process and the output suffered; things were harder to build, and they turned out worse.

Unfortunately, try as we did, those explanations were summarily dismissed. It was just like the Mario Kart conversation from earlier; why could you possibly want to go off the track? You’re not supposed to do that!

To the powers in that company, Tailwind was the be-all, end-all solution. In their minds, anybody who didn’t like the arrangement didn’t understand, didn’t know what they were doing, or were just griping about being forced to learn a new approach.

They couldn’t fathom the downsides.

In the months that followed, many of my colleagues transferred to other teams in other areas of the company. Some (like me) left entirely. That admittedly wasn’t my main reason, and I suspect it wasn’t anyone else’s either. But still: being creatively stifled by people who don’t try to understand your problems and don’t really trust that you even know what you’re talking about to begin with…well, it has a way of sticking with you.

I think often about what I could have said in those conversations; what might have made those more senior developers in charge of our projects understand the lose-lose situation they’d put us into; painted the promising sunrise they saw on their side of the mountain as the long, dark, ominous shadow we saw on ours.

I don’t know if I could have. But since I’ve spent so much of this post talking about upsides and downsides, and how one person’s bug is another person’s feature, let’s close on that.

The two sides of the same coin

Where you might see a helpful copilot who keeps you on the track, I see a meddler who gets in the way at the worst possible moments.

Where Tailwind ostensibly saves you from context switching, it keeps me away from the places where I do my best work.

Where you see a tool that helps you get through a part of the job you either aren’t best at or just don’t enjoy, I see a missed opportunity for us to collaborate and put both our skillsets to optimal use. (I also see a cheapening of what I do; your code is considered important; mine is just something to be plowed through and done well enough to move on.)

Where you see a solved problem, I see tech debt that simply hasn’t come due yet; where you saw how easily and quickly you could write something the first time, I know from painful experience how difficult it will make future refactors and rewrites.

Where you see a tool that promises freedom, I see a lock-in mechanism that will be incredibly harrowing to undo.

Where you see easy prototyping and fast styling, I see a tool that’s railroading us into speed-running making all the same web pages and interfaces everybody else is, too.

Where you see complexity simplified, I see a once-powerful tool, dulled and watered-down almost beyond recognition.

Where you see empowerment, I see suppression. Where you see protective walls, I see a constricting cage.

We’re both just observing the same truths from different points of view.

We’re both wrong. We’re both right.

It just depends how we intend to navigate the course.